Plandemic, an explosive, documentary-style video about COVID-19, spread online like wildfire. Despite its outlandish claims and obvious falsehoods, plenty of Americans were taken in by it. Because it had what so many wanted — a salacious web of conspiracy theories implicating governments, media, and public health experts — and what they needed: a story they could latch onto.

The following piece served as the basis of an Aug. 6, 2020, Purple Strategies webinar with Peter Loge, director of the Project on Ethics in Political Communication at The George Washington University, and Purple’s Denise Brien, Alec Jacobs and Meghan Moran. A recording of the webinar is available here.

Telling Stories to Explain Our World

What we know of the global COVID-19 pandemic inspires fear: millions of confirmed cases, a death toll in the hundreds of thousands, near-record unemployment, entire industries devastated. And what we don’t know suggests chaos, a world out of control: continuing questions about how the virus is transmitted and who is most at risk, uncertainty about treatments or prevention, when we can return to normalcy, or even what “normal” will mean in a post-pandemic world.

Making Sense of the World Through Stories

It’s natural that most of us are trying to make sense of the situation and navigate this chaos as best we can.

In this regard, our collective effort to process what the pandemic means and respond to it is nothing new – people strive to make sense of chaotic situations. We bring, or assert, order to our world so that we know how to function in it. The pandemic, compounded by civil unrest, political discord, climate change, and a range of other issues, makes this particular time feel more uncertain than others before it. Our urge to create an explanatory framework may be more acute than at other times. But the need itself is familiar.

One of the ways we make sense is through stories. Rhetorical scholar Walter Fisher argued that rather than homo economicus, carefully weighing pros and cons to make abstract rational decisions, people are homo narrans, relying on familiar narratives to explain our world. We identify good guys and bad guys, we assign motives, determine causes and consequences, and predict what is likely to happen next. If you strip out the details of some of the world’s most iconic stories, you’ll find many of the same core elements: a victor, a victim, and a vanquished – a heroic figure who rescues terrified villagers besieged by a dragon. Joseph Campbell, in his 1949 work “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” describes the familiar narrative this way: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

The stories we tell need not be fully accurate, but just accurate enough; facts don’t do much to inform the core of our stories. The facts matter of course, but only as much as we’re able to knit them together to help us make sense. Stories omit some facts, and others get tweaked or dialed up or down to keep the story compelling and coherent. A story can’t be entirely fictional, but it need not be entirely factual either. The story just has to be “true enough” for its listeners to recognize the kinds of tropes and motifs they expect and need to hear.

A challenge of COVID-19 and the global pandemic is that the story is an unfamiliar one. The origin of the virus is unclear, the spread is uncontrolled, the cure is unknown, the consequences keep getting worse, and the (unknown) end is nowhere in sight. That’s why our need for a compelling and comforting story is even greater. We want a story to help us make sense of the pandemic. We want a beginning, a middle, and most of all a happy ending. Just as any port will do in a storm, any story will do in a pandemic, so long as it has those familiar elements that help us make sense of things.

Enter Plandemic

In May, weeks after many Americans began social distancing and quarantining, for how long no one knew (or knows), a 26-minute video began to spread rapidly across social media platforms. In it, a filmmaker named Mikki Willis and a widely discredited scientist named Judy Mikovits weave an elaborate web of conspiracy theories, strung together with just enough of the truth (yes, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Dr. Anthony Fauci has worked in public health in the 1980s; yes, Bill Gates funds efforts to improve public health; yes, pharmaceutical companies aim to make a profit) to provide a plausible, cohesive narrative of the pandemic: what it is, what you should do, who to blame for it, and importantly why it’s happening. The video attracted millions of viewers before it was removed from platforms like Facebook and YouTube for containing medically unsubstantiated information.

The video has been criticized by the public health community, thoroughly debunked by a wide variety of news outlets, and described by scientists as nonsense at best, dangerous at worst. And yet, many people fell for Plandemic. Why?

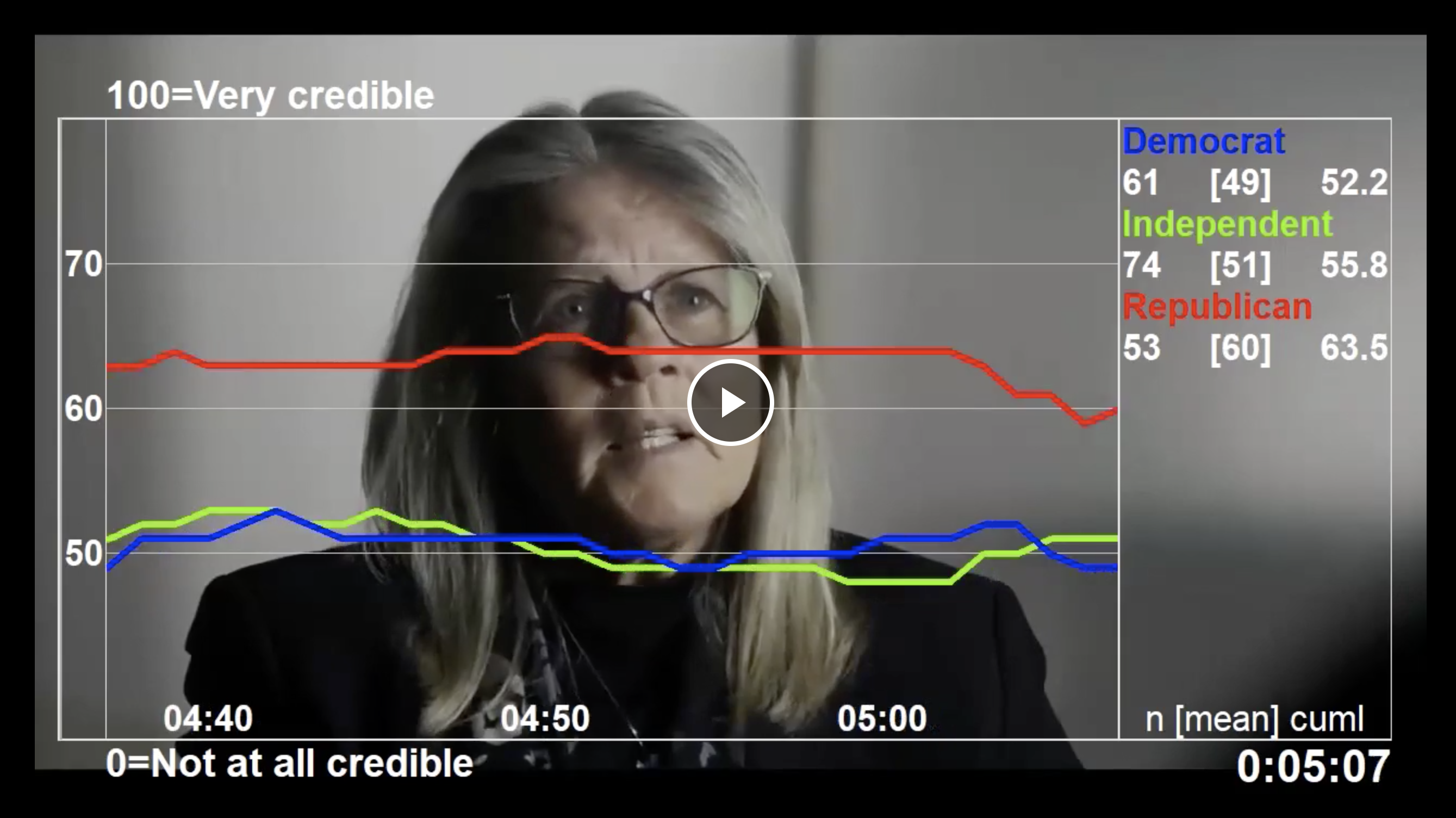

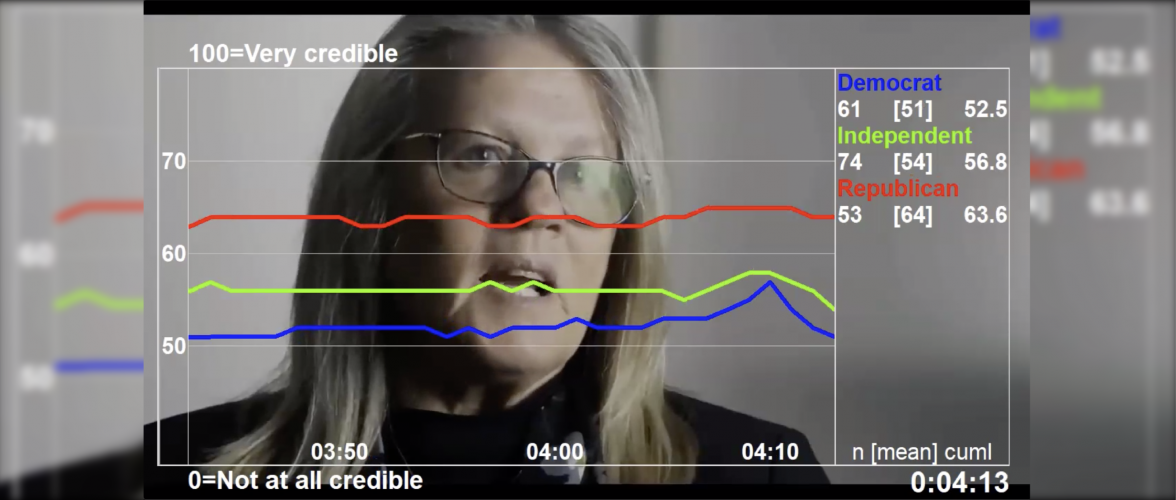

Purple Strategies’ interest in this topic is not new – our firm has been studying how misinformation spreads in an effort to help our clients navigate its often-damaging impact on corporate reputation. To understand the impact and influence on those who watched Plandemic, Purple Strategies conducted online dial testing of the full video in early June 2020 – several weeks after the video first appeared and shortly after it was removed from social media sites. In addition to dial testing, which allows the viewer to provide moment-by-moment feedback on live and recorded video content, participants in this study also answered survey questions about their beliefs and reactions to claims made in the video both before and immediately after watching Plandemic.

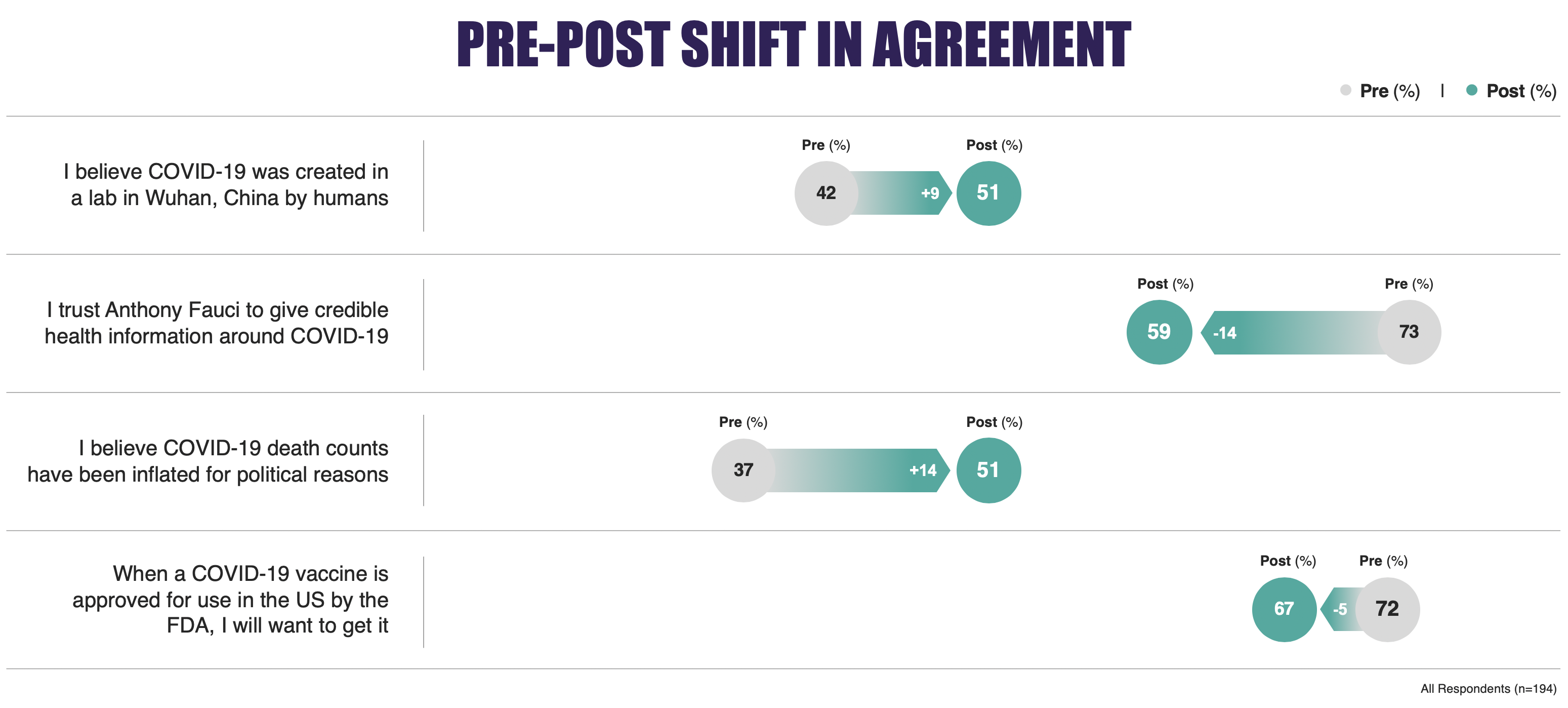

We found that the video was successful in shifting people’s beliefs (that is, their assessment of the “facts”), even among those who found the video on the whole less than credible and those ideologically predisposed to doubt the video’s claims. And while the rest of this analysis focuses on the ways and reasons why Plandemic worked, we should note that not everyone was convinced by the video – or perhaps more accurately, not everyone found the video credible. In our testing among members of the Informed Public, more than two-thirds of Democrats and Independents, and one third of Republicans, found the video to be not at all credible or had mixed opinions. And yet, many viewers – including some of those who did not find the video credible – ended up shifting their beliefs on some crucial questions about the origin of the virus, politicization of death counts, trust in Dr. Fauci, and comfort in getting the forthcoming COVID-19 vaccine.

Respondents across every demographic and psychographic subgroup shifted in their beliefs on these points, including education level, party ID, age, gender, and overall credibility of the video.

Respondents across every demographic and psychographic subgroup shifted in their beliefs on these points, including education level, party ID, age, gender, and overall credibility of the video.

How Plandemic Did It

Which brings us back to, why was this video so effective? Telling a compelling story, it turns out, was key.

(1) The video cleverly contains all the trappings of a legitimate documentary. Archival news coverage and decades-old videos and photos of some of COVID-19’s key players, particularly of Dr. Anthony Fauci. A sympathetic interviewer, nodding along in solemn agreement as his subject decries all the forces that have been at work against her. Use of scientific terms and references to other pandemics (Ebola, SARS, HIV) that signal “this person knows what she’s talking about.” B-roll footage with voiceover were made to look like news reports.

Dial testing suggests that these elements work on different audiences in different ways. Among those already sympathetic to the central arguments presented in Plandemic (those whose pre-video survey responses reveal stronger agreement with claims made in the video), assessments of the video’s credibility steadily increase as each of these legitimizers play out on screen. Among those who do not start out (or for that matter, end up) as believers, and whose dials indicate that they are increasingly skeptical of what they are seeing and hearing, they nonetheless find just enough legitimate moments to prevent them from turning their dials down into “not credible at all” territory.

Dial testing suggests that these elements work on different audiences in different ways.

(2) As homo narrans, we humans use familiar narratives to help make sense of the world. Plandemic is chock-full of familiar narratives, and there’s a little something recognizable and believable in it for everyone. Examples of claims made in the video include:

- Scientific journals twist findings that don’t agree with the narrative of the scientific community

- Tech platforms are in on the conspiracy and working to silence “dissenting voices”

- Schools don’t receive critical funding unless they “speak the party line”

- Closing the beaches to stop the spread is “insanity” because of the “sequences in the soil” and “healing microbes in the ocean”

- Pharmaceutical companies are suppressing natural remedies and therapies for COVID-19 because they won’t profit from them; with COVID, “the game” is to push vaccines

- Makers of COVID-19 vaccines will kill millions “as they already have” (though Mikovits insists she’s “absolutely not” anti-vaccine)

- The outbreak of COVID-19 began not only in Wuhan but also in a lab at Ft. Detrich, in Frederick, Maryland, suggesting that the US military-industrial complex is partially responsible for the virus

- The government is inflating the death toll of COVID-19

- Fauci is at the center of a vast coverup conspiracy (though what he is covering up is not clearly defined)

These are effective precisely because they tap into deeply held, longstanding beliefs and reinforce familiar narratives; the sheer volume and ideological range of the claims increase the chance that everyone can find something in the video that aligns with something they already believe to be true. We know that people across demographic and psychographic groups are susceptible to misinformation, even and especially the smartest among us. Plandemic proved no exception. For those on the right, COVID-19 claims are overblown, tech platforms are suppressing the truth and China is largely responsible for the outbreak; for the left, big pharma is bad and “real” science is under attack. And for those, left or right, who are attracted to conspiracies in general, the idea that elites (in the media and science) are perpetrating a cover-up is salivating. These narratives provide just enough of a “hook” to shift people’s beliefs pre/post video on several of the video’s central claims.

(3) The video gives us the story we crave in its most traditional form. The hero — Judy Mikovits — aims to save her village — the world! — from a dragon — a “plague of corruption that places all life in danger.” Despite many trials and tribulations — Mikovits claims to have been arrested and terrorized by agents of the government and “minions of Big PhRMA,” and accuses Dr. Fauci of covering up a major scientific discovery she made — Mikovits’ “courage” to speak out helps the hero ultimately prevail. But perhaps more importantly for understanding how this and other misinformation like it succeed, the story we crave is a story, any story, that helps us make sense of that which seems to make none, providing a ready explanation of what this is, who has been wronged, who is responsible, and how we should proceed. Not everyone is convinced by this story, but that really isn’t the point. The real, accurate story is messy – doctors, nurses, and public health officials striving to figure out the virus, treat it, and cure it against a backdrop of conflicting messages about transmission and prevention. The true story lacks the clearly defined narratives and roles we crave – victor, victim, vanquished. Plandemic provides those comfortable tropes.

“I find it what we need to hear. We always need to question what we’re being told. The content of this doesn’t surprise me.”

“I have seen this video before and shared it on social media as I thought there was good information to share. I was told that the scientist was fake and her research is discredited and not valid. However if people do not want information shared they cover it up. We all need to research information that we read and hear and not take things for face value.”

“The lady sure appeared sincere, knowledgeable, and credible. There are some folks that need to be required to answer some really tough questions.”

“I am so glad I saw this video and I find it very credible, interesting and educational. It is scary how our government can hide things and control people and situations in cases like this.”

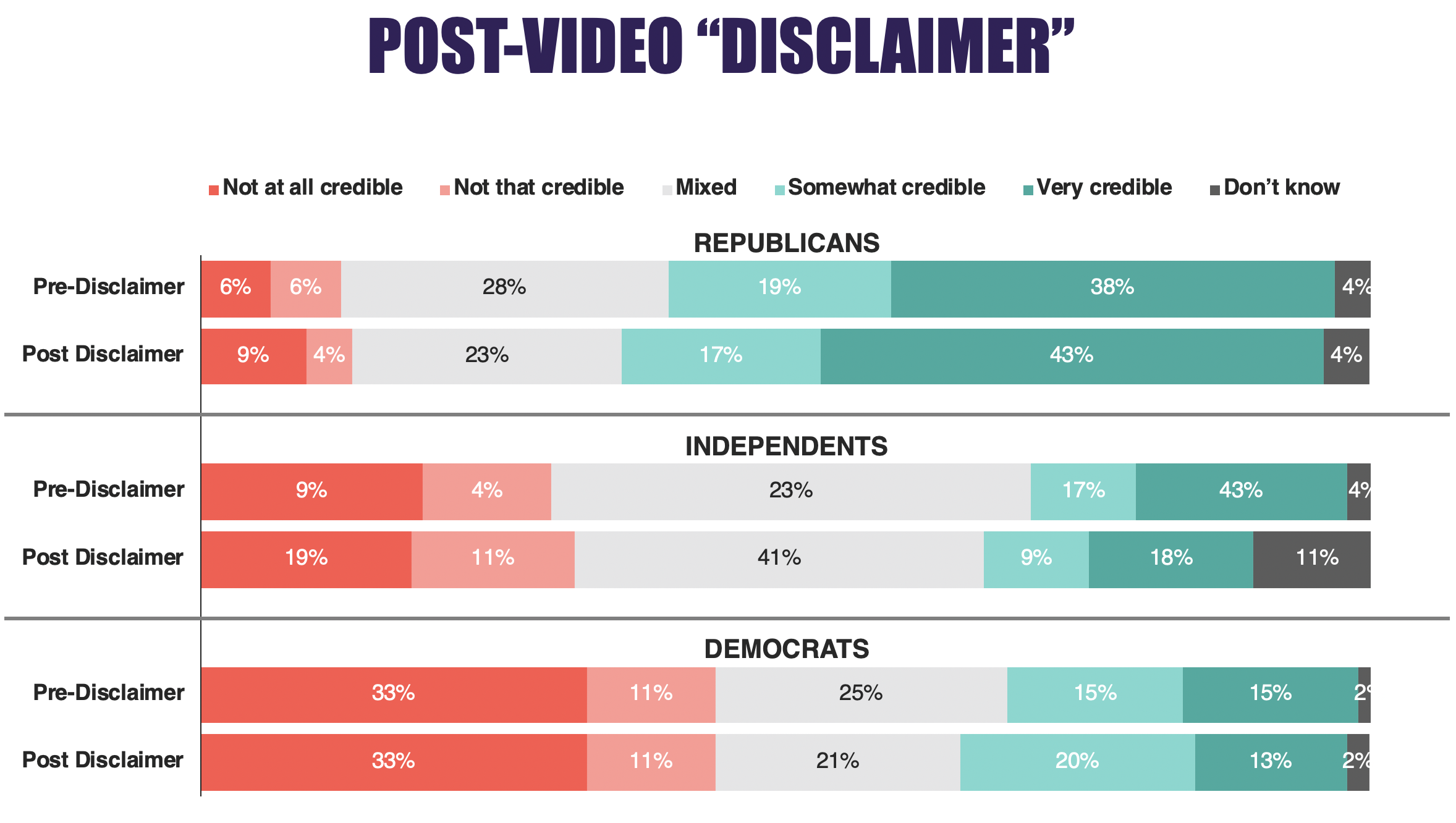

(4) The video trusts us to make the right decision with the “truth” it has revealed to us. People don’t want to be told what to believe. They want to make up their own minds and come to their own conclusions. The creators of Plandemic lay out plenty of “facts” and the story they’re telling is clear, but they stop short of telling viewers exactly what to believe or how to act. This is especially important because we know how severely it can backfire when people are told what they should believe. The last question of our survey showed people a disclaimer informing them the video they had just watched was removed from social media sites for containing misleading information and asked how credible they found it knowing that. It turns out that the disclaimer didn’t shift people’s overall assessment of the video’s credibility, and open-end responses suggest that knowing that the video had been taken down actually caused some respondents to find it more credible. Though they were attempting to do the right thing, this move by social platforms actually increased resistance and skepticism, lent further credibility to the idea expressed in Plandemic that the actual truth was being hidden.

Q: In light of the information that social media platforms removed this video from their platforms because it included unsubstantiated medical advice, how credible do you find the information shared in the “Plandemic” video?

How to Fight Back

Immediately after Plandemic was posted online, multiple media outlets and critics (with arguably far more credibility and bona fides than the protagonist of Plandemic) mounted a spirited rebuttal, offering point-by-point takedowns of the factual inaccuracies in the video. Their intentions were good: correct the record and provide people with more accurate information so they can make better decisions and come to more informed conclusions. And while there has been some scholarly debate about how well that works, recent research has shown that fact-checking can work to sway people’s beliefs in the direction of new, more accurate information.

But countering a conspiracy theory requires more than facts and fact-checking – it also requires its own compelling narrative. Disputing a conspiracy theory fact-by-fact can help weaken its credibility, but without a supporting story that presents accurate information in a compelling narrative, it will usually lose. Good advocates provide accurate information with the contents – the narrative – to help make sense of complex and sometimes evolving facts.

What this suggests is that to counter misinformation, we need a more compelling counter-story. And in this respect, Plandemic offers valuable lessons for all of us:

• Meet people where they are. Attempting to change people’s beliefs (assessment of the facts) and ultimately their attitudes (underlying position on a topic) requires first understanding their starting positions and beliefs. Too often, fact-checking makes the mistake of assuming that people are looking for truth, when more often they are looking for confirmation and validation; too often counter-arguments jump to the “right answer” without considering the barriers many will have in making such a leap. Moving people to another position often requires an incremental approach that recognizes where they are now in terms of their beliefs and plans the steps (including new information) it will take to bring people along.

• Tell a story. Facts and rebuttals may be the basis for the story we want to tell, but they cannot themselves be the story. A list of facts is not a story. Critical facts must be woven together into a story that makes sense of the chaos and confusion. They must offer a better port.

• Use narratives that give people something familiar to latch onto. Particularly in stressful and uncertain situations, we seek out the familiar to comfort us. Plandemic deftly employs familiar narratives that speak to different audiences at different starting points, giving just about everybody at least something they can nod along with.

• Find the right storyteller. Perhaps the biggest challenge for those looking to combat misinformation is that they are so often missing a compelling and credible voice to tell their story. With the increasing politicization of science, hyper-partisanship in politics, and the active and increasing distrust of companies and institutions, this is not an easy task. And it is made even more difficult by those who spread mis- and dis-information, who typically look to discredit messengers of truth as a first step. Dr. Fauci might have been well-positioned to tell a comprehensive story about the pandemic and how we can eradicate it; the filmmakers’ direct and repeated attacks on him were certainly no accident. Scientists are often called on to rebut inaccuracies, but can make for less than compelling messengers by virtue of the self-restraint imposed by their ethical and moral responsibilities and obligations to the scientific method and the communication of scientific findings. They may make good messengers, if they can communicate authoritatively and responsibly in a way that is still compelling.

• And finally, guide people toward the truth but let them come to their own conclusions. Attempts to force people to accept a particular belief or story as true often backfire. People trust themselves to sort through evidence and reach the right conclusions much more than they trust others. The decision about what to ultimately believe and accept must be theirs. Unfortunately, this kind of encouragement to “decide for yourself” often takes the form of telling people to question everything and to not accept anything as true until they’ve done their own research, which is what leads many down conspiracy theory rabbit holes to begin with. But by supplying people with the facts they need woven into narratives they’ll recognize and accept as legitimate, and guiding them toward trusted sources for affirmation, we’ll have done what we can to help people come to sound conclusions.

Denise Brien | Managing Director | denise.brien@purplestrategies.com

Alec Jacobs | Senior Director | alec.jacobs@purplestrategies.com

Peter Loge | Associate Professor, School of Media and Public Affairs, The George Washington University | biography

Purple is actively partnering with companies and industries to navigate the impacts of misinformation and disinformation, bringing deep experience helping the world’s best-known companies navigate the world’s toughest challenges. Please reach out to authors Denise Brien or Alec Jacobs or any member of our Purple team to let us know how we can support you.

Your Earnings Call Just Testified Before Congress. Were You ...

Your Earnings Call Just Testified Before Congress. Were You ...  How can you hit the bullseye during the big game without bec...

How can you hit the bullseye during the big game without bec...  Patients Aren’t Patient Anymore

Patients Aren’t Patient Anymore  Washington’s New Normal: Why the Old Advocacy Playbook No Lo...

Washington’s New Normal: Why the Old Advocacy Playbook No Lo...